Contents:

- What are bee boxes and what do they do?

- The history of using boxes to manage beehives

- Using bee hive boxes to manage colony growth through the seasons

- Parts of a beehive

- Types of bee hive boxes

- Plastic vs. Wood beehives

- Beehive Maintenance

- FAQs

What is a bee box and what does it do?

“Bee box” is a commonly used term for the physical structure that houses a bee colony. A “colony” is a collective organism made up of a single bee family, consisting of one queen, drones and thousands of worker honeybees, while a “beehive” is the structure that houses them.

In the wild, many native bee species create their own homes, known as nests. Honeybees that are tended by humans are housed in manmade structures called beehives. The technical term used by beekeepers and bee scientists for what laymen call a “beehive” is a “hive body”.

–– Interested to know how the bees are doing? Download our State of the Honey Bee Report now ––

The history of using boxes to manage beehives

Mankind has been gathering honey from honeybees for more thousands of years, with the first image of wild honeybee harvesting coming from cave paintings in Spain dating from 8,000-6,000 BCE. The first tended hives are believed to have occurred around 2,500 BCE in Egypt and possibly earlier in China. From the time of the ancient Egyptians to the 18th century, beekeepers captured swarming bees and kept them in skeps — iconic structures most often made of woven, stacked rings of rushing or straw that form a pointed dome. Skeps are still used in rural areas in the developing world. They’re hollow inside, with no internal structure other than the sides of the skep for bees to build comb. While simple and inexpensive to construct, they offer beekeepers no options to help the colony grow and store its honey. When skeps reach capacity, the colony divides in two, and the old queen leaves with half the bees to form a new colony — the process we know as swarming. To extract honey from the skep of the original colony, beekeepers must break it open and remove the honeycombs, effectively destroying the old colony.

Better solutions were experimented with in the late 18th century by Francois Huber and early 19th century by Thomas Wildman. Huber built what he called a “leaf hive” made of book-like leaves, stacked vertically, that could be removed to extract honey without destroying the colony, and Wildman developed a “bar hive” with vertically hung bars, where comb could be built by bees and removed by beekeepers. While promising, neither of these solutions was widely adapted by beekeepers.

In the mid 19th century, the Reverend Lorenzo Langstroth, an amateur beekeeper in Pennsylvania, discovered that bees couldn’t create comb in spaces less than 1 centimeter from each other (about 3/8”). With this knowledge, Langstroth designed a hive with wooden frames hanging exactly 1 centimeter apart. These frames were perfect for bees to build comb on, and beekeepers to remove for honey harvesting. Langstroth’s hive design made it easy for beekeepers to manage hive growth — as brood and honey stores increased, beekeepers could add frames within the box, and once nearing capacity, could add more boxes, producing the stacked box approach used today by most beekeepers.

Using boxes to manage colony growth through the seasons

As the seasons progress, the needs of the colony for temperature control and space for brood tending and food storage change. Beekeepers respond to this change by adding or removing frames and bee boxes as needed to help optimize the size and health of the colony. Bees naturally create a kind of “balloon space” within the hive, and the beekeeper’s goal is to stay ahead of need and give the colony the right amount of space to maintain that balloon shape as the colony ebbs and flows.

Under more predictable seasonal patterns in the past, bee boxes were added to hives in spring and summer as brood size increased and nectar flows allowed bees to produce ample honey supplies and removed in early fall as colony size declined and honey was consumed. With changing and often erratic weather patterns caused by global warming, spring may come much earlier than in the past, warranting early hive expansion. Hot, dry summers and violent storms can lead to habitat loss, significantly reduced nectar flows, and honey production. The prevalence of pests can reduce brood size as well. All these factors can lead beekeepers to reduce the number of frames and bee boxes in the middle, rather than the end of the season.

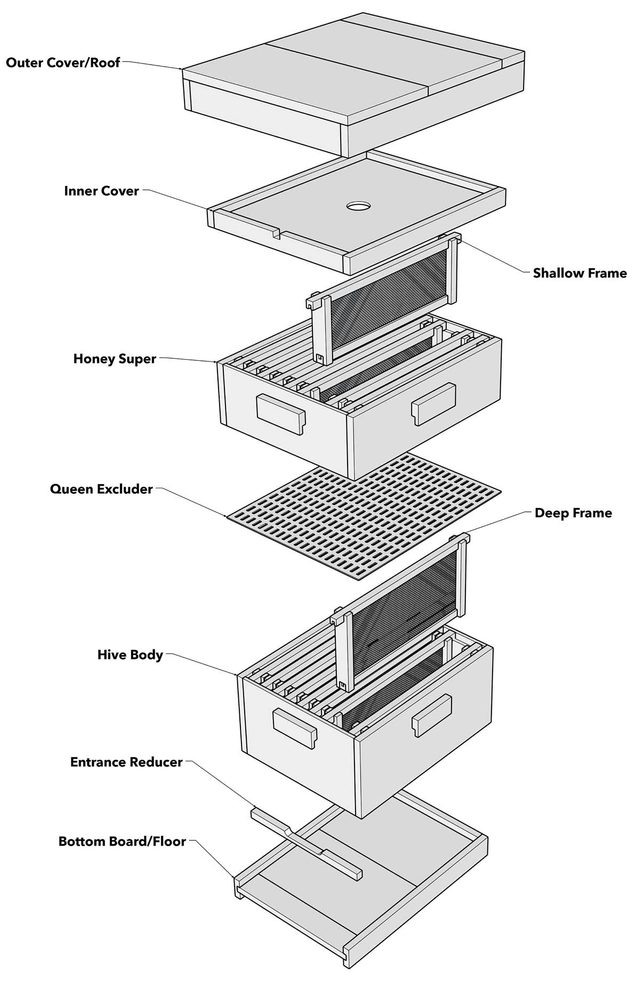

Parts of a beehive

Most beehives consist of 5-10 distinct parts that provide structure for the colony to store food and tend brood, as well as provide protection for the colony from the elements and from predators. If a beehive is a house for bees then each part of the hive has a function like the parts of a human house.

- Stand: The stand is the footing of the hive upon which the hive, consisting of a bottom board and one to three bee boxes—the basic external structure of the hive—is built.

- Bottom Board: The bottom board is the floor of the hive, and includes the entrance, or “front door” for the bees to enter and exit the hive.

- Supers: The term super refers to bee boxes which are stacked on top of the Bottom Board.

- Deep Super: Sometimes called the “hive body” or “brood box”, a deep super is where the bees raise their young and first store honey.

- Medium & Shallow Supers: These are smaller in height than the deep super (hence the names) and sit on top of it, holding most of the harvestable honey.

- Frames: Frames are hung vertically within each box, and so function like the studs that create inner walls within a house. In a beehive, they’re moveable, and so can be shifted from center to side within a box, and from top to bottom box, as needed for hive management.

- Foundation: Foundation, made of beeswax or plastic with embedded wire frames, is like the finished walls on which the bees hang their combs. Foundation is installed on the sides of the frames to encourage bees to make straight combs that are easily removed. Worker bees build brood cells and as well as honeycomb on the foundation.

- Inner Cover: An inner cover sits on top of the uppermost honey super. This has evolved over the years, starting from protection from weather to adding increased management options like a 2nd entrance or ventilation. Insulation, if used, is put on top of the inner cover.

- Outer Cover: Sometimes called at telescoping top, the outer cover acts as the roof of the hive. It’s usually made of wood, like most hive parts, and is covered with metal. The top has sides that hang a few inches down the sides of the top bee box, to prevent water from entering the hive.

- Security Straps and Weights: These are straps or ropes that wrap around the hive on the side of a hive from top to bottom and back to the top to protect it from being opened by predators or the wind. In some cases, a weight or stone is placed on the top of the hive instead of straps for the same purpose..

- Queen Excluder: Not used by Best Bees, queen excluders are wire or plastic mesh that’s hung between the brood box and the honey supers to keep the queen from entering the honey supers and laying eggs there. The mesh in a queen super is designed to allow smaller worker bees to pass through and build honeycombs in the honey super, which can be harvested later by the beekeeper, without damaging any brood.

- Entrance Reducer: This is a small block of wood which reduces the size of the entrance to the hive, helping to control ventilation in cold weather, and protecting it from robber bees.

Types of bee hive boxes

Langstroth

The most popular with beekeepers, and the type used by Best Bees. Langstroth beehives are usually made of wood and consist of stacked supers sitting on on a bottom board. The advantages of Langstroth hives are the removable frames, which make it easy for beekeepers to inspect the hive, make adjustments, and harvest honey without hurting the bees.

Top Bar

This is one of the oldest types of hive. It usually has no foundation and is basically a triangular wooden box on legs with wooden bars along the top of an open cavity. It requires a lot of active management to keep the comb straight, but its advantage is it’s very easy to add or restrict space to match the size of the colony. Extracting honey from top bar hives is difficult, as there are no extraction tools designed for them.

Warre

The Warre hive is like a hybrid of the Langstroth and the Top Bar. Like the Langstroth, it’s built of stacked boxes, but unlike the Langstroth, it’s stacked from the top down. Like the Top Bar, it offers bees hollow cavities to build comb in. Most Warre hives include a quilt box filled with wood shavings that help insulate the hive and reduce moisture. The proponents of Warre hives prefer them because their design mimics the natural places that honeybees nest and allows them to build comb the way they see fit. Unfortunately, Warre hives are Illegal in most states because their design makes it impossible to remove frames and do a thorough inspection for disease.

Horizontal or Layens Hives

Sometimes called a long hive, these are similar to Langstroth hives, and use the same standardized materials, but rather than being stacked vertically, they’re built horizontally. Designed by 19th century French beekeeper Georges de Layens, the advantage of this hive type is that there is no lifting of boxes—which can be quite heavy when filled with honey—during hive inspection and management. Horizontal hives are much less common than Langstroth, making them more expensive to purchase and their replacement parts harder to come by.

WBC Hive

Also known as a British Standard Hive, the WBC (named after designer William Broughton Carr) is made up of parts similar to the Langstroth hive but includes an outer “lift” or tapered box that provides insulation, sheds water, and protects the weaker wooden boxes on the inside of from weathering. The tapering sides of each box give the WBC hive its classic pagoda look. WBC hives are more expensive to build than Langstroth hives.

Flow Hives

These contemporary hives are designed to make honey extraction simple. They contain plastic comb that bees fill and cap, and a mechanism that breaks the wax caps and allows the honey to flow out into a container, without opening the honey supers. Traditional beekeepers are opposed to the use of plastic, but the plastic used is BPA free, and has no effect on aroma or taste. High cost of purchase is the primary negative to this type of hive.

Apimaye Hives

These were designed to be an evolution of the Langstroth hive, using similar design, but improvements such as insulated walls, food-safe durable plastic construction, better ventilation, and a bottom board that includes a varroa mite excluder screen. In the event of colony loss, the materials used in this hive allow for sterilization before a new colony is introduced. The only negative to Apimaye hives is their high cost to purchase.

Plastic vs. Wood Beehives

At Best Bees, we prefer wood over plastic beehives, because they’re made of renewable materials, they’re recyclable, repairable, light, and less expensive.

Here are the pros and cons of each:

Pros of wood hives:

- Made of natural, renewable materials that can be recycled at the end of their use.

- lighter, and easier to lift and move than plastic.

- Can be disassembled and easily repaired.

- Pine (the most common wood used in beehives) imparts a subtle scent to the honey.

- Less expensive to purchase.

Cons of wood hives:

- Warp and split more easily and require more repairs.

- Harder to clean.

- Wax moths can burrow into them.

Pros of plastic hives:

- Much more durable than wood.

- No assembly required.

- Wax moths can’t burrow into them.

- Easier to clean.

- Easy to spot pest eggs, especially against black plastic.

Cons of plastic hives:

- More expensive to purchase.

- Difficult to recycle.

- When foulbrood, a destructive disease of honeybee larvae caused by bacteria, appears, the hives must be treated with expensive radiation to clean them.

- Bees can sometimes reject plastic hives.

Beehive Maintenance

If well maintained, wooden beehives will last for 8-10 years, depending on weather conditions. Hive maintenance is relatively simple: the biggest issue facing hives is moisture, which is bad for both the wood of the hive and the bees themselves. Coating the outside of the hive with either paint or polyurethane as needed, and assuring proper ventilation, will reduce moisture and the likelihood of wood rotting.

With monthly hive inspection, beekeepers can identify problems in the hive, and if damage has occurred, easily repair or replace parts.

FAQ’s

Q: Is there a difference between a beehive and a bee box?

A: Beehives and bee boxes are the same and refer to the physical structure that houses a living bee colony.

Q: Which is better, wood or plastic?

A: Both wood and plastic have their advantages and disadvantages. At Best Bees, we prefer wood because it is renewable, repairable, recyclable, light and inexpensive.

Q: What is the best type of beehive?

A: Each type has its fans, and while each has distinct advantages, the Langstroth hive, which we use at Best Bees, is the most popular. It’s easy to maintain, easy to manage, and is less inexpensive than most of the alternatives.

Q: Do people still use bee skeps?

A: Traditional bee skeps—straw rings woven into the iconic pointed dome—are still used in rural areas in the developing world, because of their low cost. They’ve been replaced everywhere else because there is no way of removing honey from a skep without destroying the colony.

Q: How many boxes should a beehive have?

A: The number of bee boxes will vary by the size and condition of the colony. Typically, hives start with one or two boxes in the spring and add one or two as the colony grows and honey production increases. Late in the season, as the colony reduces, boxes are removed.

Q: Can you paint a bee box?

A: Yes, the outside (never the interior) of bee boxes is usually painted or coated with clear polyurethane—this helps keep moisture out of the hive and prevents rot. Use exterior latex paint with low levels of VOCs (volatile organic compounds), and allow the hive to expel paint gas for at least a week before introducing bees

If you live in a hot climate, consider painting your hive boxes in light colors to reflect the sun, and help keep them cool. In climates with cold winters, darker colors absorb sunlight and can help warm the hive.